Film Reviews: Maestro & Monster

The Love that Dares not Speak its Name.

Maestro & Monster

By Marc Glassman

Maestro

Bradley Cooper, director and co-script w/Josh Singer

Starring: Carey Mulligan (Felicia Montealegre Bernstein), Bradley Cooper (Leonard Bernstein), Matt Bomer (David Oppenheim), Maya Hawke (Jamie Bernstein), Sarah Silverman (Shirley Bernstein), Michael Urie (Jerome Robbins), Josh Hamilton (John Gruen)

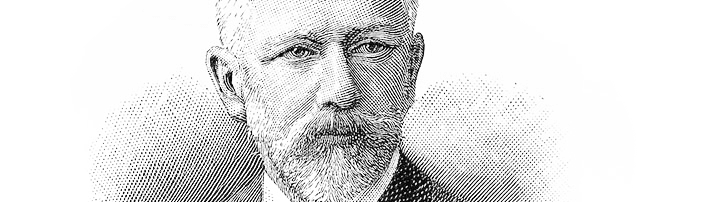

Leonard Bernstein led an extraordinary life, worthy of many films. Most of us would love to see a movie concentrating on Bernstein’s public persona as a brilliant conductor—the first American to lead a major symphony, the New York Philharmonic–and educator, whose performances, many captured on radio and TV, and lectures on classical music and conducting, famously presented on the CBS national broadcast series Omnibus, are still impressive and enlightening so many years later. There could be another film, which would investigate Bernstein, the extraordinary composer of the musicals On the Town and West Side Story, the score for the classic Marlon Brando film On the Waterfront, ballet music for Fancy Free and The Dybbuk, three symphonies, choral music, fanfares and numerous journeys into such styles as hymns, prayers and sonatas. And then there could be a shorter piece on Bernstein, the humanist and radical, who worked tirelessly with Communist sympathizers, civil rights activists and anti-war demonstrators. Or another on Bernstein, the lover of the high life of New York society, the orchestrator with his wife Felicia of myriad dinner parties and attendee of important galas for decades. Truly, Bernstein was a man who encompassed multitudes.

Bradley Cooper’s film on Bernstein tries to embrace all of the contradictions in the astonishing life of the American Jewish musical genius, but his approach is quite a bit different than one might assume. Maestro, despite the title, is less about Bernstein the musician and much more on the bisexual figure who loved his wife and children but remained attracted to men throughout his lifetime. It’s the Lenny, who passionately embraced love in its many forms that forms the drama in Maestro, and while the music isn’t downplayed, it isn’t the focus of the film. If there is music at the core of Cooper’s concept of Bernstein, it’s the sad, tantalizing melodrama of a woman who loved one man, and the maddeningly ambiguous response of that person—Bernstein—to her love.

Bradley Cooper, with gentlemanly aplomb, gave the wonderful actor Carey Mulligan the lead cast credit for her performance as the gifted gorgeous Felicia Montealegre, who married Bernstein in the early Fifties and remained his wife until her death in 1978. During that quarter of a century, the elegant actress eventually put aside her career to take care of the Bernstein’s three children and devoted herself to leftist causes and membership in Manhattan’s stylish elite, which she and her husband both embraced. She was, in a phrase, “the perfect partner” for Bernstein, the beautifully dressed and supremely intelligent wife to the esteemed conductor and composer, who was by his side at endless social, humanitarian and musical events.

Cooper not only plays Leonard Bernstein in Maestro, but he’s also the director, co-author and co-producer of the film. This is his vision of the great musical figure: a man of beguiling charm, personal conviction and dedication to his craft, who is immensely conflicted in his private life. When Lenny and Felicia meet in the mid-1940s, they’re so young and gorgeous and terrifically talented, that it seems that what we’re seeing is a true love match. But what we’re looking at is a complex set of images. Yes, they adore each other but it’s never going to be enough for Leonard Bernstein, who was always a gay man. Like many homosexuals over the ages, he was able to function sexually with a woman, but that would never wholly satisfy him. This becomes the central dilemma of Maestro: how do the Bernstein’s remain together when an essential element in their relationship is unfixable?

Bradley Cooper has made a stylish film, which evokes the post-war era when Manhattan was on par with Europe in its fashion, music and glamour. The first half of the film, mainly rendered in black and white is wonderfully hectic: we see the 25-year-old Leonard Bernstein replacing an ill Bruno Walter, and scoring a conducting triumph on the stage with the New York Philharmonic; that’s followed by his meeting with Felicia at a party hosted by the brilliant pianist Claudio Arrau; they fall in love and, in an almost hallucinatory scene, participate in a clever pastiche of the three sailors dancing in a Manhattan club to music composed for On the Town. It’s all too exciting, too much fun—but it does give one the sense of a love affair that could sustain a relationship for decades.

Unfortunately, black and white footage is replaced by colour as the pace slackens and the Bernstein family—now with children—negotiate their life in their palatial estate in Connecticut and beautifully appointed apartment in Manhattan. The children, particularly the eldest daughter Jamie, begin to hear rumours about their dad, and Felicia starts to become unhappy with Leonard’s “sloppy” indiscretions. What had been private was now all too public in an era—the Sixties and Seventies—when many secrets were revealed. Maestro charts this sea-change and shows the marriage splinter—although in the end, the love between Leonard and Felicia is proven to be true.

Maestro is a very well-made film. Bradley Cooper spent years learning how to conduct and play the piano properly. His accent reminds one of Leonard and even the problematic use of prosthetics to construct a more Semitic nose for Cooper is hardly an issue. Carey Mulligan is terrific as Felicia and will undoubtedly score an Oscar nomination. (Will she win? Who knows?)

But—and I think you knew there would be a “but”—is this the Leonard Bernstein we wanted to see? I must confess to being disappointed in a film on Bernstein that doesn’t dramatize the creation of West Side Story. And doesn’t even show anything from On the Waterfront. We’re missing the Leonard Bernstein film I wanted to see.

As for Maestro: it’s very good but not enough. We need more about Lenny and less about the marriage. Full confession: I love Carey Mulligan. But this film should have been more balanced, with more music, maestro!

Monster

Hirokazu Kore-eda, director

Yuri Sakamoto, script

Ryuichi Sakamoto, music

Starring: Sakura Ando (Saori), Soya Kurokawa (Minato), Hinatat Hiragi (Yori), Eita Nagayama (Mr. Hori), Yuko Tanaka (Fushimi, the principal)

The much-lauded Japanese filmmaker Hirokazu Kore-eda is an artful humanist, defiantly making tender films in these difficult times. His brilliant film Shoplifters, about a highly functional family of modern-day outlaws defying society’s codes was a breath of fresh air, when it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes five years ago.

It focused international attention on Kore-eda, whose films work against standard narrative expectations, finding love in situations where tragedy could easily beckon. He delights in setting up stories in which the audience can expect bleak results, and then offers hope instead of tears. Most of his major films, such as Shoplifters and his recent Korean success, Broker, give prominence to children, whose vulnerable status pivots much of the emotion in his complicated plots.

Monster is a typically complex tale by Kore-eda, offering a plethora of characters, all of whom have secrets, but are attempting to function well in a society that that will never truly accept them. Saori, a single mother operating a dry cleaner, is concerned when her 11-year-old son Minato comes home from school with cuts on his ear and obvious signs of abuse. To Saori, who dearly loves her son, it’s clear that Mr. Hori, an unstable school teacher is targeting her son, making his life miserable. But confronting the school’s hierarchy proves dissatisfying as the principal, the enigmatic Ms. Fushimi, offers complete surrender, obviously forcing Hori to apologize abjectly. What Saori wants is an explanation for her son’s problems at school, but none is forthcoming though her pleas for understanding couldn’t be more straight-forward.

Kore-eda has structured Monster elegantly, with the same story being told from different perspectives: first through the eyes of Saori, second, as it was played out from Mr. Hori’s perspective and third, from the point-of-view of Minato, the supposed victim, and his best friend, Yori. The obvious comparison to Kore-eda’s approach is Akira Kurosawa’s in the legendary multiple perspective drama, Rashomon, in which the same robbery-murder-rape is recounted by four narrators, each with a different version of the tale.

While some stories are clarified in the multiple recounting of Minato’s dysfunctional relationship with Mr. Hori, a deeper story is slowly revealed. The central question in Kore-eda’s narrative is this: why does an 11-year-old think of himself as a monster? Slowly, with a deference to the ambiguous play of pre-teen boys, a truth is revealed: Minato and his best friend Yori care for each other, perhaps “too much.” In the conventional society, where Canadians and Japanese dwell, their affection is still not acceptable.

Let’s be clear: nothing explicit happens in Kore-eda’s hugely empathic treatment of a growing affection between two naïve boys. What’s lovely is how much fun they have together playing games on an abandoned train, decaying in the mountains near where they live. What’s tragic is the anger and fear that is dramatized as the two act out their natural emotions towards each other.

There is a tentative nature to Monster, which is unlike Kore-eda’s recent quite confident work. Perhaps he, too, wants to shy away from the implications of a film that explores adolescent love—and what is supposedly monstrous—by offering a dream-like conclusion to his tale. Leaving the film ambiguous will likely make Monster more accessible on the international market. It’s certainly worth mentioning that Kore-eda garnered yet another prize at Cannes for Monster, this time for best script (with Yuri Sakamoto).

Monster has the qualities that should make it a hit. Let’s help to make it happen.